On our return trip to Argyll in 2018, we discovered a wide variance in pronunciation between residents of the various Gaelic Hebridean islands, and among locals in west Scotland as well. Take, for example, a seemingly straightforward word like "Ledaig". Ledaig, of course, is an exceedingly fine Islands scotch crafted in Tobermory, on the Isle of Mull).

|

| March 2018 Tobermory Distillery |

Impassioned assurances from various regional Gaelic people, that they themselves pronounce this or that word correctly versus all those "others" in Gaeldom who do not, was somewhat a tap-in-the-ribs type of humor, albeit good-natured. Even so, how they understand each other is a mystery.

These introductory comments on "fluid" Gaelic spellings and pronunciations are applicable to Kilchiaran chapel. Reconciling the chapel's namesake saint is also quite an exercise. Variously known as: Chiaran, Ciaron, Ceran, Kieran, Kyran, Queran and more besides, the identity the specific saint is tricky.

These introductory comments on "fluid" Gaelic spellings and pronunciations are applicable to Kilchiaran chapel. Reconciling the chapel's namesake saint is also quite an exercise. Variously known as: Chiaran, Ciaron, Ceran, Kieran, Kyran, Queran and more besides, the identity the specific saint is tricky.Kieran was apparently a very popular name among early Irish saints...a dozen or more have the name. And several are alleged to be contemporaries. Case in point is St. Kieran the Elder and St. Kieran the Younger.

Kilchiaran Chapel on Islay is presumed to have been named for one of these two Kierans. And most accept Kieran the Younger as the namesake saint. But that is not entirely certain.

"Historical" accounts (the few that exist) actually commingle the lives of these two saints. For example, Life of St. Kiaran (The Elder) of Seir translated in 1895 from earlier Irish accounts records these two saints together, with St. Patrick as well.

But if true, given the timeline broadly attached to Kieran the Elder, that necessarily would have made him very advanced in age at the time of his death, accounts imply he was born in 402 A.D. and is generally thought to have died in 527 A.D. In contrast, most accounts claim Kieran the Younger died at a comparatively young 30 years of age. Considered to be a contemporary friend of St. Columba, Kieran the Younger's lifespan is roughly bracketed from about 516 to 550 A.D.

A few accounts (likely mistaken, having been compiled several centuries after) claim Kieran the Younger died in the "Yellow Plague". This is mentioned because a century (+/-) difference in dating these two saints (and many others in this period) may exist. Their lifespans are difficult to reconcile because error has been introduced due to the expanse of time (a few centuries) between the lives and the medieval writers who later chronicled them.

Yellow fever was not introduced into the British Isles until 664 A.D.--a full century after St. Columba founded Iona, the mother church of Scotland. The date is fairly precise, because it occurred after a solar eclipse in May of 664. Yellow fever continued to extract an extremely high mortality toll in the British Isles for more than two decades. Thus, it would have been a widely known historical event to the later medieval biographers who sought to chronicle the lives of the early Irish saints.

This 20 or 25 year outbreak of yellow fever actually did kill off most of the Irish monastic community of Clonmacnoise (which Kieran the Younger is credited with establishing). And thus, the error is understandable in retrospect.

|

| Accounts commingle the lives of the two St. Kierans/ |

A last observation from the Life of St. Kieran the Elder is entirely speculative on my part. And it is a wild speculation that I have not seen in academic print anywhere.

At Kilchiaran chapel is found what is called a "cup-marked stone". It is recumbent and considered to be "earth fast"...being in the same place it was when the cups were marked. Cup marked stones exist widely over west Scotland, some dating fairly deeply in the Mesolithic Age, to perhaps as late as the Bronze Age. They were used in religious rites, of some sort, possibly grinding botanical compounds or grains. No one is certain, but these cup marked stone rites were probably on the order of prayers of hope and supplication, as practiced (previously mentioned in a post here) at Kilchoman...in a relict social practice originating from time immemorial.

The ancient graveyard at Kilchiaran is laid around this cup marked stone. Thus, the site on Kilchiaran Bay has been long revered and recognized, perhaps several thousands of years before the Kilchiaran chapel was established, allegedly by St. Columba. Many, and perhaps most, early Christian chapels were established on sites that were known to be sacred to prehistoric people.

In any case, the cup marks on the stone, bear some resemblance to the constellation Orion. Whether or not that is significant, is unknown. (It was mentioned in a previous post on Finlaggan that the Cnoc Seannda standing stone apparently marks the rise of the constellation Orion in mid winter.)

My wild speculation takes into consideration a curious account found in the Life of St. Kieran the Elder. The account, with an imagination, may actually relate to the cup marked stone at Kilchiaran.

|

| A reference to the cup marked stone a Kilchiaran perhaps? |

The account mentions Sancta Coinche, who is called St. Kieran the Elder's "nurse". In modern terms, Coinche would have been Kieran's foster mother. According to the account, Coinche used a big stone "to practice imploration and prayers".

That stone, was "at some distance from the monastery on the strand of the sea"...which more or less does describe the cup marked stone at Kilchiaran Bay on Islay, if one takes strand to mean a beach. The cup marked stone at Kilchiaran is lying on a raised shingled beach, below but included within the chapel's burial ground.

|

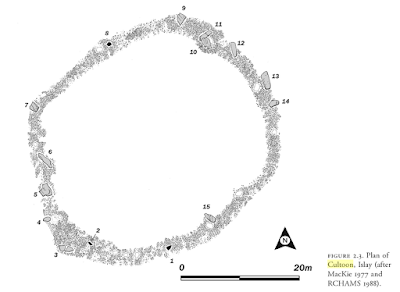

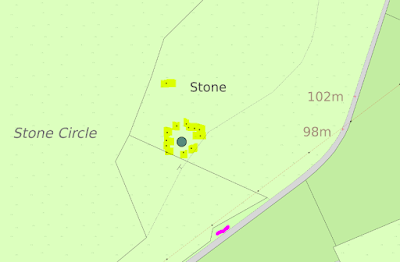

| From Canmore; location of cup marked stone at Kilchiaran |

He stated that Coinche's Rock was to be found on the banks of the Fergus River near Ennis in County Clare, Ireland. What Rev. Mulcahy did not say is that he had located this rock, or had seen it.

At Ennis, a Franciscan friary did exist; but this was first built c. 1250 A.D., easily some 700 years after either of either of the Saints Kieran.

Rev. Mulcahy suggested the specific location of Coinche's Rock was at Cuinche, which today is known as the village of Quin. An abbey also existed at Quin; but its construction began in 1402 A.D. at the request of the Franciscan abbots at nearby Ennis.

Whether or not a tradition regarding Coinche's Rock was subsequently established at these mid and late medieval monastic communities, is not known. No evidence of any reference is known to me (other than Rev Mulcahy's translation notes) of the existence of Coinche's Rock at Quin. Perhaps jaded, but surely if Coinche's Rock did exit there, it would have long ago been advertised. Pilgrimages were, and are, big business to local economies.

Rev. Mulcahy noted that writers have made "a medley of mistakes regarding the nurse, St. Coinche, and her place". Many presume that Coinche's Rock must have been located in Ireland. But, could that also be mistaken?

This stone of imploration and prayers could indeed be the cup marked stone at Kilchiaran, at some distance from the monastery on a strand of the sea, just across the Irish Channel.

|

| March 23, 2017 Kilchiaran Bay, Islay |